The selection of artwork for commercial spaces is sometimes an afterthought. Individuals may choose pieces based on how they complement a palette, or they prioritize their personal taste over the setting and its users. Also, artwork in these spaces often lacks the framing provided by museums and galleries. In those contexts, historical and cultural interpretation explain an artwork’s importance. The relevance of artwork in places where it’s not the main attraction can be more difficult to grasp beyond ‘a nice picture on the wall’.

Yet, art doesn’t lose its significance in workaday places. A work of art in an everyday setting is also a product of history and culture, but attitudes about where art with a capital ‘A’ belongs relegates it to the realm of décor – implying that it’s less meaningful and important. In a discussion about aesthetic deprivation in clinical settings, Hilary Moss and Desmond O’Neill argue that this separation between fine arts and the everyday is artificial and limiting (Moss & O’Neill, 2014). The everyday objects we encounter, including art, can enhance our appreciation of our environment and enrich us.

For example, artwork programs for senior living environments present unique opportunities and challenges. As residences, they need to feel like home to individuals with different personal, social, and cultural understandings of the term. As healthcare institutions, they ideally enhance the well-being of residents and optimize the therapeutic benefits of the environment for people with differing levels of physical and cognitive competence. Additionally, they need to consider the needs of staff and their well-being.

A thoughtful approach to artwork selection starts with understanding “that the physical, social, organizational, and cultural environment are deeply interwoven” (Wahl & Weisman, 2003). It acknowledges that spaces within a campus may require different types of artwork depending on who uses it and what activities take place there, while still maintaining a cohesive sense of place. With this in mind, selected artwork can address concerns such as aesthetics, wayfinding, well-being, values, culture, and branding. Artwork can be more than ornamental. It can help create an environment that is supportive and stimulating for residents and staff alike.

References

Hilary Moss and Desmond O’Neill, “The Art of Medicine: Aesthetic Deprivation in Clinical Settings,” The Lancet, Vol 383 (March 22, 2014): 1032-1033.

Hans-Werner Wahl, PhD, and Gerald D. Weisman, PhD, “Environmental Gerontology at the Beginning of the New Millennium: Reflections on Its Historical, Empirical, and Theoretical Development,” The Gerontologist, 43 No. 5 (2003): 616-627.

Canter, David V. “The Facets of Place.” In Psychology in Action. Hantshire: Dartmouth Publishing Company, 1996), 107-138.

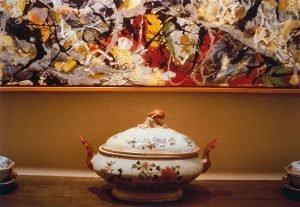

Louise Lawler, Pollock and Tureen, Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut, 1984. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tracing the movement of works of art as they make their way through galleries, museum storage, auction houses, and private homes, Lawler captured this image of a Jackson Pollock painting in the Connecticut home of collectors Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine.

Louise Lawler, Pollock and Tureen, Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut, 1984. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tracing the movement of works of art as they make their way through galleries, museum storage, auction houses, and private homes, Lawler captured this image of a Jackson Pollock painting in the Connecticut home of collectors Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine.